History of the Eucharistic celebration II: the Semitic heritage

Monday, October 28, 2019

*Rogelio Zelada

In the absolute silence of the immense room, the voice of Moses resonated, strangely confident amid the sacred splendor of the audience with Pharaoh: “The God of the Hebrews has come to us. Now let us take a three-day journey into the wilderness to offer sacrifices to the Lord our God.” The Exodus story repeats the same request over and over again: Let my people go to offer me worship in the desert.

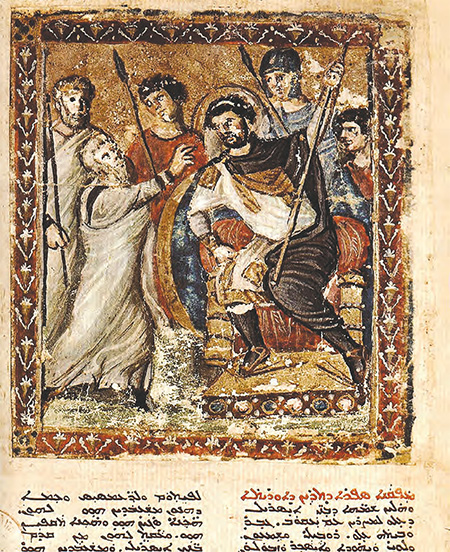

Moses before Pharaoh, miniature, 6th century AD, Syriac Bible

The setting for the ancient celebration of nomadic shepherds had to be the solitude of the flowered desert. New life was celebrated there: The equinox that gives rise to spring, the time when the sheep bore lambs and fresh herbs decorated endless fields. For those tribes, that was the sign that the God of their Fathers celebrated the anniversary of creation and the beginning of history, a fundamental event that had to be treasured with the communal renewal of an alliance of love. A beautiful, strong and tender animal, the best, should be offered in sacrifice. Its blood, extremely sacred, especially since it came from an animal consecrated to the Lord, could not be consumed. Spilled on the sand, it was used to paint the poles that held up the tents, to scare away the unclean spirits which caused diseases.

On that extraordinary night, the men, sitting in a circle around the fire, recalled the great actions carried out in the daily life of the tribe by the presence of the God who journeyed with them, a story full of emotion and solemnity, entrusted to the elderly, the ones who preserved the memory of the community.

The dinner in the desert marked the beginning of the New Year, a new cycle. That night they would march with their flocks after dinner, under the light of the new moon, en route to the new camps surrounded by good pasture and abundant water, pastures and water that the scouts had already located. The lamb was consumed simply roasted on the fire because all the utensils had already been put away. The sharing of that sacred meal was a participation in a sacrifice of communion because sharing an animal offered and sacrificed to the Lord and Redeemer brought them intimately together in a one-of-a-kind contact, in an extraordinary blessing of closeness.

The father of the tribe was to ensure that everyone could participate in the sacrifice; it was his turn to cut the meat of the lamb into pieces not smaller than an olive. Thousands and thousands of years later, when the presider breaks the bread in the liturgy of the Eucharist, the assembly sings “Lamb of God,” evoking the fracturing of the paschal lamb.

The side dishes at this cheerful dinner were herbs or tender vegetables that could be found in the environs at that time of year. It was consumed with everything ready for the trip, wearing work clothes and shoes suitable for the long journey, with the fabrics, tent posts and kitchen utensils tied up along with the family’s trousseau. They then walked to the new camp under the bright light of the full moon shining over the desert.

The story in chapter 12 of the Book of Exodus adds, to the ancient traditions of nomadic shepherds, the rites with which the farming peoples celebrated the New Year. For them, the chosen sign was the feast of Azyms, the beginning of the year, with new grains, seeds and, above all, bread, toasted on the stone with no remnants of the old yeast. These two traditions were united in one during the reform of King Josiah.

The entire historical evolution of Israel left its mark on the blueprints used for celebrating the annual Passover. Like all festive meals in Israel, it was fundamentally a sacred act. Every meal is always sacred; the one that starts the Sabbath is extremely sacred, a sacredness surpassed only when Passover falls that year on a Saturday. A structure was gradually established, the Seder, which has remained almost unchanged throughout the centuries.

When Cyrus, the great king of the Persians, allows the Hebrews to return to the Promised Land, only the Jews return, resolved to rebuild their lives around the Temple of Jerusalem. At that time, after captivity and exile, the only thing that remains of all the territory once occupied by the kingdom of David are the ruins of the Holy City and its surroundings.

Passover, the celebration of the great deliverance from slavery in Egypt, and the birth of the people of the holy covenant, evolves from the rite of a family meal in the house where they usually live, into the great annual pilgrimage of all Hebrews to Jerusalem, in whose temple only the high priest could sacrifice the paschal lamb.

Comments from readers