By Cristina Cabrera Jarro -

Photographer: COURTESY PHOTO

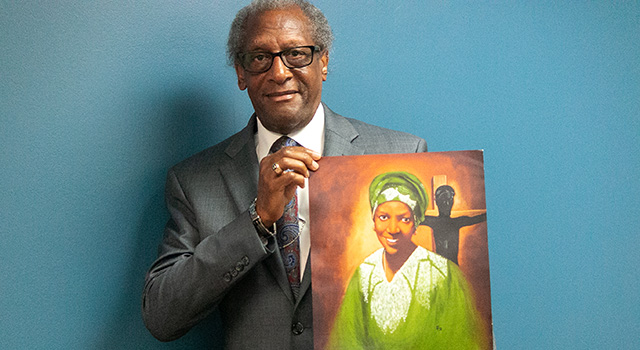

This portrait of Sister Thea Bowman, of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, painted by Alexander Moore, was given as a gift to her friend, Donald Edwards, assistant superintendent of schools at the Archdiocese of Miami. Sister Thea has been declared a Servant of God, and is one of six Black Catholic candidates for canonization.

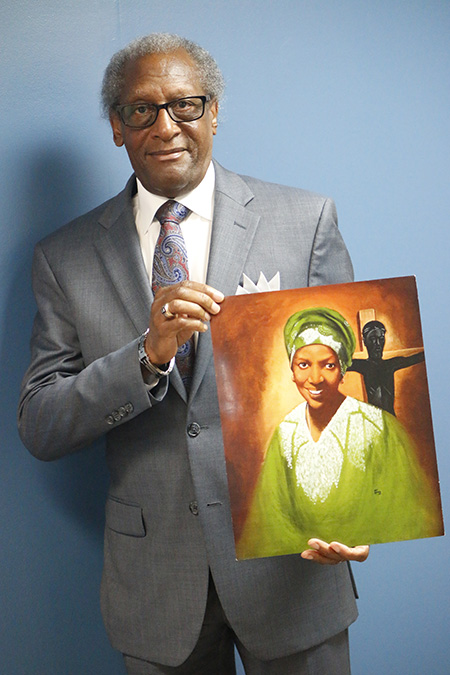

Photographer: ANA RODRIGUEZ-SOTO | FC

Donald Edwards, associate superintendent of schools for the Archdiocese of Miami, poses with an image of his good friend, now Servant of God Sister Thea Bowman.

MIAMI | An acquaintance of Donald Edwards once pointed out to him that he must walk around glowing because he had a personal relationship with Sister Thea Bowman, who, in 2018, was declared a Servant of God — the first step on the journey to canonization.

“I didn’t even think about it. Thea was just Thea,” said Edwards, the Archdiocese of Miami’s associate superintendent of schools. “But when you think about it, it just blows you away. I had the privilege of actually walking in the shadow of this woman who will be a saint.”

A granddaughter of slaves, and the only Black woman in the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, Sister Thea was first a teacher, and later an advocate for racial justice. She spoke across the country in gatherings that combined Gospel teaching, prayer, storytelling, and music.

It was through those events that she crossed pass with Edwards. In the 1980s, his pastor invited Sister Thea to host an evangelization event at their parish, St. Michael Church in Memphis, Tennessee. Edwards was principal of the parochial school, and having a background in music, got involved.

“Thea and I spent a significant amount of time together working and planning this. I put together a huge choir made up of members from Catholic church choirs from all over the city. I arranged several Negro spirituals and pieces of Gospel music,” said Edwards.

Though the parish and school community were predominantly white, he remembers a very welcoming reception for Sister Thea and “a packed house” at St. Michael’s. People loved her and asked when she would return. Whenever she did, she drew out a big crowd not only of Catholics, but also Baptists, Methodists and Episcopalians from churches nearby.

“When Thea came to Memphis, people from all around wanted to come see and hear her,” said Edwards.

Those moments helped their friendship blossom. During her visits to Memphis, Sister Thea invited Edwards to the home of her cousins, Sally and Carl Bowman.

“Sally would cook collard greens, candied yams, potatoes, baked chicken or turkey: soul food. And we would eat and enjoy each other’s company,” said Edwards.

Afterwards, they sat outside on the porch to birdwatch.

And there was always music.

When Sister Thea’s health declined because of breast cancer, Edwards would drive to her home in Canton, Mississippi, bringing a keyboard along to liven her spirits and “old musical soul.”

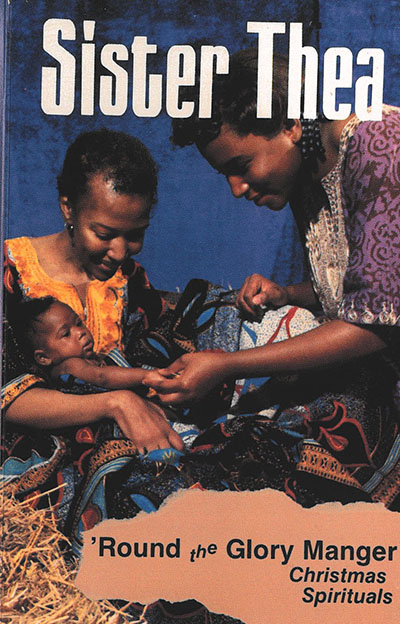

Photographer: COURTESY PHOTO

Sister Thea Bowman carries a child on the cover of the Christmas spirituals album she recorded, "Round the Glory Manger." She used music learned from her grandparents, family, and others, to share the Gospel. Sister Thea has been declared a Servant of God, and is one of six Black Catholic candidates awaiting canonization.

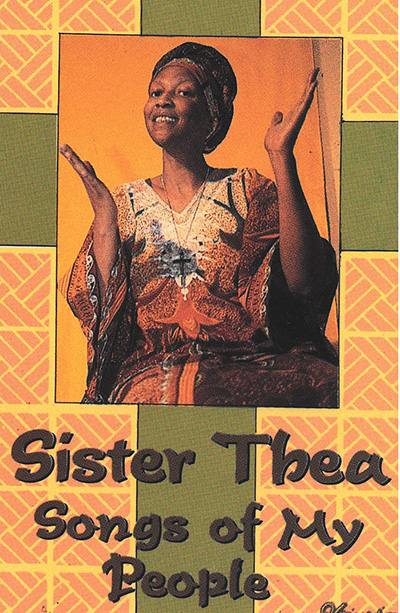

Photographer: COURTESY PHOTO

With palms raised, Sister Thea Bowman posed for the cover of the album she recorded, "Songs of My People." Throughout her life, Sister Thea used music to evangelize and bring awareness of the history and needs of Blacks and Black Catholics. She has been declared a Servant of God, and is currently one of six Black Catholic candidates awaiting canonization.

“We’d sing songs and just play all day, praise God, and enjoy each other’s company. Thea sang songs that, as she would say, 'the old folks sang.' She had excellent sostenuto, and just a beautiful soprano voice,” said Edwards.

She also enjoyed being in the company of old Black people. Their wisdom and character helped shape her pride as a Black woman growing up through the civil rights movement in the United States.

“The stories that they told, the songs they sang, the experiences that they had. I would have feared had she gone to the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration that she was going to lose her blackness, her love for 'the mud of Mississippi,' her love for the music of Southern Black people. But, of course, she didn’t,” said Edwards.

Originally raised a Protestant, Sister Thea converted to Catholicism at the age of nine. But she shared her roots when she sang Negro spirituals or “slave songs,” hymns, and gospel music that she had learned from her grandfather, Mama Tolliver and Mrs. Garrett, who were slaves, as well as her mother and countless others. In her album “Songs of My People,” the music mentioned Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Noah, Moses, David and Jesus.

“They used the sacred songs to teach Scripture and faith and values and love and dedication. They used the songs to teach responsibility and prayer. Sharing the songs of faith bonded us in family and church. Sharing the songs brought hope and consolation and joy. The songs of faith are my heritage,” wrote Sister Thea.

In 1989, she became the first Black woman to address the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. Speaking candidly, she asked them, “What does it mean to be Black and Catholic? It means that I bring myself, my Black self. I bring my whole history, my traditions, my experience, my culture, my African American song and dance and gesture and movement and teaching and healing and responsibility as a gift to the Church.”

By then, Sister Thea was wheelchair-bound because of her advanced cancer. But that did not slow her as she spoke about the need for the bishops to welcome and support a stronger presence of Blacks in the Church.

“If we, as a Church, walk together, don’t let nobody separate you. That’s one thing Black folk can teach you. Don’t let folks divide you... The Church teaches us that the Church is a family, is a family of families, and the families have got to stay together. And we do know that if we do stay together, if we walk, and talk, and work, and play and stand together in Jesus’ name, we’ll be who we say we are: truly Catholic,” said Sister Thea.

From there, she led the assembly in singing “We Shall Overcome,” an anthem of the civil rights movement. According to Sister Charlene Smith, a friend of Sister Thea who coauthored her biography, after the speech every bishop came to Sister Thea, knelt, and asked for her blessing.

“She was a holy woman, and it was powerful to be around her and spend time with her,” said Edwards.

But it never occurred to him to ask her about one day becoming a saint. “I would have loved to have heard her response to that. She probably would have said, 'Yes, if saints ate collard greens.'”

After her death in 1990, Edwards began the Sister Thea Bowman Sacred Music Festival at St. Michael’s in Memphis. He invited choirs from all over the city to an annual “packed house” event. He also invited Sally and Carl Bowman to speak about the life of their religious cousin. The festival continued until Edwards left St. Michael's to become principal at Memphis Catholic High School.

But the friendship that bound him to Sister Thea remains. “Thea was certainly an inspiration to me. And I pray to her, as do many people.”

FIND OUT MORE

- The lives of Sister Thea Bowman and the other five African American candidates to sainthood are explored in a three-part online webinar that began Nov. 7 and will continue Nov. 14 and 21 from 3 to 4:30 p.m. Register at: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/122107178859.

- For more information on Black Catholic History Month, contact Katrenia Reeves-Jackman, director of the archdiocesan Office of Black Catholic Ministry, at 305-762-1120 or [email protected].