Wednesday, March 9, 2022

Jim Davis - Florida Catholic

MIAMI | Ukraine’s relationship with Christianity goes back centuries, perhaps even starting with one of Jesus’ 12 disciples. Unfortunately, the land has also been a site for invasions, oppression and tensions between branches of Christendom.

Photographer: Jim Davis | FC

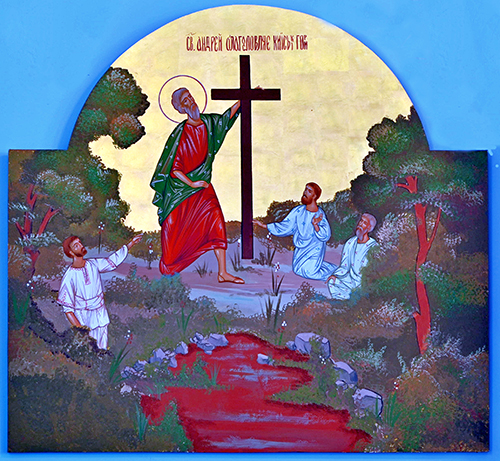

St. Andrew blesses a cross in what is now Ukraine. Tradition says that Andrew, one of the original 12 disciples, preached in the region north of the Black Sea.

Tradition says that St. Andrew traveled north of the Black Sea and preached there. Saints Cyril and Methodius followed up in the ninth century by adapting a specialized alphabet from Greek. Called the Cyrillic alphabet, it fueled Ukrainian literacy and scholarship, and it’s still used by Slavic peoples.

By the 900s, there was at least one church in Kyiv, in what is now the capital of Ukraine. Queen Olga accepted Christianity and was baptized in the 950s, but the breakthrough came with her grandson Volodymyr (known in Russia as Vladimir).

Prince Volodymyr examined several religions of his time and fell in love with the eastern Christianity of Byzantium for the ethereal beauty of its liturgy. He renounced paganism and accepted baptism in 988 – then had everyone in Kyiv baptized in the Dnieper River, which runs through the city. That led to conversion in other Slavic lands, in what are now Russia and Belarus.

His kingdom followed Byzantine Christianity in the Great Schism of 1054, which produced what is now the Eastern Orthodox Communion. The Russian Orthodox Church then became centralized in Moscow in 1325.

Ukraine’s churches made peace with Rome in 1596, in a historic agreement called the Union of Brest. The Church became a hybrid, using the same Byzantine Rite as do the Orthodox but honoring the pope as their leader.

But the union fell apart less than a century later, and the churches divided again along East-West lines. In the 19th century, Russia’s tsarist regime forced its Catholics to accept Orthodoxy.

From there, it got worse. Starting in 1946, the Soviet government banned all expressions of Ukrainian Catholicism. Churches and seminaries were closed; priests and other church leaders were tortured, sent to prison camps or even killed.

Photographer: Jim Davis | FC

St. Volodomyr and his grandmother, Queen Olga, oversee the baptism of Kyiv's residents. Ukrainians see the mass baptism in 988 as the birthday of Christianity as the state religion.

Only after 1989, when Soviet life was liberalized, did the Greek Catholic tradition in Ukraine begin to revive. By then, many Ukrainians had fled, establishing new churches in Europe, Australia and the Americas.

Wherever they went, they made their mark. Prominent Americans of full or partial Ukrainian descent have included cellphone pioneer Martin Cooper, Hyatt Hotels founder Jay Pritzker, Vietnam War hero Myron F. Diruryk and the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

In cinema, the long list includes Dustin Hoffman, Walter Matthau, Leonard Nimoy, Natalie Wood, Sylvester Stallone and Steven Spielberg. In music, there are conductor Leonard Bernstein, folk singer Bob Dylan, and rockers Steven Tyler and Lenny Kravitz.

Others of Ukrainian origin have included Olympic skater Sasha Cohen, ice hockey player Wayne Gretzky, and the late Alex Trebek of the TV quiz show Jeopardy.

In their former homeland, the Church has helped rebuild national culture and patriotism. Today, about nine percent of Ukraine’s 43 million people are Greek Catholics in communion with Rome. They live mainly in the western region near Poland, but hundreds of thousands also live in Kyiv and the Black Sea port of Odessa.

Some persecution returned in 2014, when Russia seized and annexed the Crimean peninsula. Some priests there were imprisoned briefly, and the churches had to change their names to avoid using the word “Catholic” together with “Ukrainian.”, according to Father Andrii Romankiv of Miami’s Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Ukrainian Catholic Church.

Step 2 for Russia was to foster separatist movements in two regions of eastern Ukraine, even declaring them independent nations as a pretext for supplying military support. Father Romankiv and other church leaders have warned of more repression ahead.