By Marlene Quaroni - Florida Catholic

Photographer: MARLENE QUARONI | FC

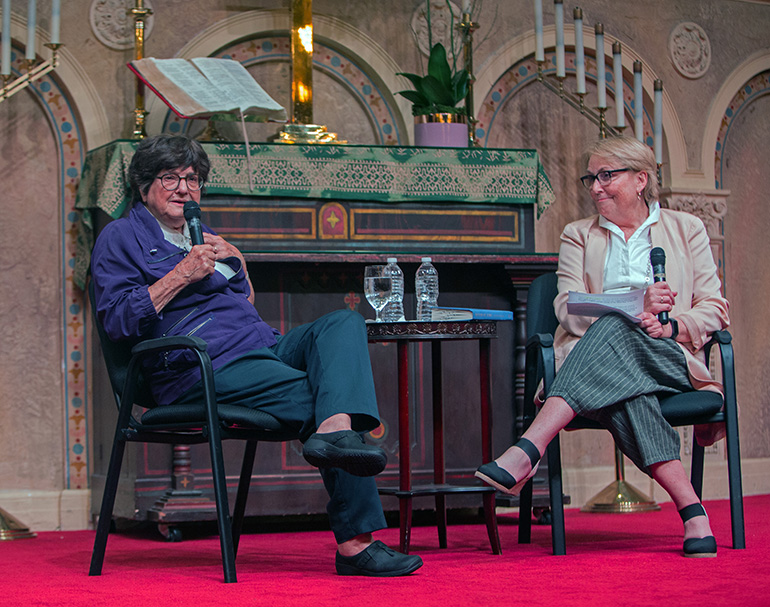

Sister Helen Prejean, of the Congregation of St. Joseph, discusses her new book with Coral Gables Congregational Church's senior pastor, Dr. Laurie Hafner.

CORAL GABLES | Sister Helen Prejean didn’t hear the cry of the poor until she got Jesus right.

“I didn’t hear their cry right there in New Orleans, with 10 major housing projects filled with struggling African-Americans,” said Sister Prejean, 80, in her Cajun accent, during a discussion with Coral Gables Congregational Church’s senior pastor, Dr. Laurie Hafner.

About 100 people attended the talk Aug. 15 in the church. Sponsored by Books and Books, it was one stop on her nationwide tour for her new book, “River of Fire,” a memoir of her spiritual journey. The Sister of St. Joseph has authored two other books, “Dead Man Walking” and “The Death of Innocents.”

Photographer: Marlene Quaroni

After her talk, Sister Helen Prejean consoles Melissa Bouie, whose uncle is on death row in Missouri.

“Dead Man Walking” was about her relationship as spiritual advisor to Elmo Patrick Sonnier, a convicted murderer awaiting execution at Louisiana State Prison-Angola. The book was number one on the New York Times best-seller list for 31 weeks and was made into a movie in 1996. Susan Sarandon, who played Sister Prejean, won an Academy Award for Best Actress.

“As I accompanied Pat and then five other prisoners to their deaths,” Sister Prejean said, “I came to know their families, as well as some of the families of the victims. Sonnier was killed by electrocution in the electric chair, fire. I was drawn into the fire that enkindled my prayers, my energy and all my efforts over the past 34 years,” she said, alluding to the title of her latest book, “River of Fire.”

Sister Prejean was 25 years into her vocation before she realized Christ’s call to social justice. Having entered the convent right out of high school in 1957, she joined a world of strict discipline and blind obedience. She wore the Congregation of St. Joseph of Medaille habit, “a long, black, widow’s garb of the 17th century,” when Father Jean Pierre Medaille organized a group of women in France into a spiritual organization.

Vatican II brought about great changes to the Church and to religious life. Old habits changed, both literally and figuratively. “A black blouse, a skirt shortened to mid-calf, perky little black heels, I felt like one mod, hip nun,” she writes in her book.

DESEGREGATION

Aside from Vatican II, there was school desegregation in the early 1960s. Sister Prejean taught English and religion at St. Joseph Academy for girls in New Orleans. Her school actively recruited African-American girls, not setting limits or admitting only a few as a token of integration. Because of those policies, the school received threatening phone calls and the sisters were called communists.

“The Ku Klux Klan burned a cross on our lawn to protest the presence of two African-American couples on the night of the junior-senior prom,” she said.

Unable to make it financially, St. Joseph Academy closed in 1979. Sister Prejean continued her studies in theology and served as religious education director at St. Frances Cabrini Parish in New Orleans, as well as director of novices for her congregation there.

Sister Prejean was in her 40s when a talk at a conference she attended on the message of Jesus Christ struck her like lightning. At first, she recalled, she wasn’t enthused about attending the conference, held in Indiana, with her congregation’s novices in tow.

Photographer: Marlene Quaroni

Beverly Ross, a former hospice chaplain, talks to Sister Helen Prejean as she signs her new book after her talk.

“It would be three whole days and nights of nothing but social justice and no chance of escape, with all of us housed in college dorm rooms in the middle of the woods. The college is not called St. Mary of the Woods for nothing,” she writes. “It’s brainwashing to get us all to be social revolutionaries.”

Sister Marie Augusta, of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur, a teacher of sociology and the New Testament as well as a full-throttled advocate of social justice, laid out the sad statistics of how unfairly the resources of the world are distributed, namely the bountiful gross national product of rich countries such as the United States and the miserable statistics of poor countries.

“I know that, I know life isn’t fair,” Sister Prejean remembers thinking. After a full day of nothing but global statistics, the talk finally got back to Jesus.

“The lightning bolt came in a mere 22 words,” she said. “The words came from Sister Marie Augusta. Jesus preached good news to the poor, integral to that good news is that the poor are to be poor no longer.”

The dignity of the poor as sons and daughters of God calls them to strive for what is rightfully theirs: justice, not charity; active struggle, not passive compliance, Sister Prejean learned. The call of Christ in the Gospel is to be involved with marginalized people and those who don’t have a voice.

HOPE HOUSE

That’s how she began her journey in social justice. Sister Prejean and another sister moved into Hope House on the edge of the St. Thomas Housing Project in New Orleans. Hope House has a food pantry, sells used clean clothes for 25 cents, provides emergency funds for rent and utilities, is a safe place where people can unburden their hearts with someone who listens and cares, houses a meeting place where community organizers can gather and strategize, and runs an adult learning center.

“The cumulative effects of generational poverty are difficult to overcome,” Sister Prejean said. “When experienced by the 10th generation in a former slave state such as Louisiana, poverty’s undertow seems so powerful that it begins to feel permanent, inevitable, a fact of nature.”

Most of the project’s residents carry sweat rags because they can’t afford air-conditioning to escape the summer heat. They are victims of poor housing and bad schools. “I watched as a kid ran a bag of white powder down the street for a quick $20. Many of the boys are in jail and the girls are teenage mothers. They face bleak prospects and intractable obstacles. Where is the American Dream?” she writes in “River of Fire.”

In August 2018, Pope Francis declared the death penalty unacceptable in all cases because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person and contrary to the Gospel of Jesus.

Photographer: Marlene Quaroni

Courtney Munoz poses for a photo with Sister Helen Prejean during the book signing.

In a dialogue with Pope John Paul II in 1997, Sister Prejean asked, whether it is only the innocent who have dignity, since Catholics readily condemn abortion yet support the death penalty.

“As I accompanied Patrick Sonnier to the death chamber, hands and feet shackled and guards surrounding him, he turned to me and whispered, ‘Please, pray God holds up my legs as I walk,’” she writes in her book. “Where’s the dignity in this death?”

In addition to advocating for the abolition of the death penalty, Sister Prejean founded SURVIVE to help families of victims of murder and related crimes.

BOOK SIGNING

A book signing followed the discussion, with some audience members asking pertinent questions, among them United States Federal Judge Pat Seitz, a member of the Miami Catholic Lawyers Guild. She said that courts are more and more opting for life sentences without parole instead of the death penalty.

A Coral Gables Congregational Church member and former hospice chaplain called Sister Prejean amazing. “I can’t imagine what it’s like for those on death row,” said Beverly Ross. “She inspires me to think about helping them. She walked with them up to the last seconds of their lives.”

Finally, Melissa Bouie stepped up to the table with tears in her eyes. She spoke to Sister Prejean about her uncle, who is on death row in Missouri. He was due to be executed by lethal injection in 2016, but his execution was stayed. His lawyer claimed that because of a medical condition the drugs could cause violent seizures. His case is being appealed.

Bouie and her husband asked Sister Prejean if she would take part in a short video so that Bouie could send it to her uncle for his birthday, August 20.

“He will be baptized on his birthday,” said Bouie. “He’s not the same person he was in 1994 when he committed the murders. I’ve learned that our worth is more than our biggest sin.”