By Rocio Granados - La Voz Catolica

Photographer: ROCIO GRANADOS | LVC

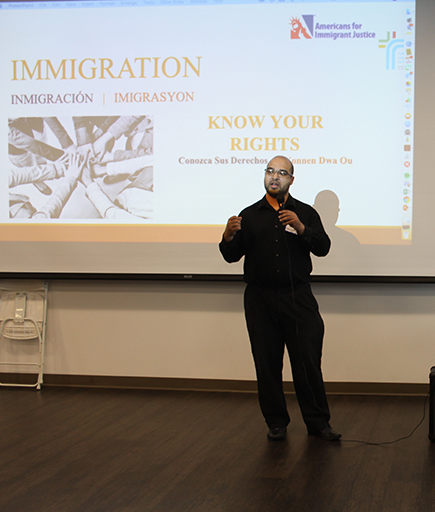

About 100 immigrants attended the Know Your Rights session organized by Catholic Legal Services, Americans for Immigrant Justice and the Don Bosco Ministry of Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, Doral, Feb. 9, 2019.

MIAMI | Currently, life in Venezuela is very difficult.

There is work “but what they pay you does not cover groceries for the week,” said Ariana Gonzalez, a young Venezuelan who arrived in Miami in October with a tourist visa.

“There is also no variety of food. If you do find some, it is very expensive, and you are limited to buying what you need most, to at least fill your stomach,” said Socorro Mendoza, another Venezuelan who arrived in Miami with a tourist visa last September.

“It is a luxury to have shampoo, deodorant or tooth paste,” Gonzalez added. You may find it “but it is impossible to buy, you won’t have enough money.”

Photographer: ROCIO GRANADOS | LVC

Catholic Legal Services attorney Felix Montañez speaks about asylum to a mostly Venezuelan audience gathered for a Know Your Rights session Feb. 9, 2019 at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, Doral.

Hyperinflation, which has increased since 2015, causes the price of goods to rise so quickly that salaries, even with raises, do not compensate enough to buy the basics.

“I fattened up here. In Venezuela, I could not stand the hunger,” said Mendoza, whose family lives close to the border with Cúcuta, in Colombia. One of her sons moved to Peru to work, and although her mother of 86 years eats well, she “is very skinny.”

The situation is more difficult than what gets reported in the media.

“In Venezuela, you do not see anything about what is really happening, we only have social media to keep us informed,” said Gonzalez. “The internet and phone lines do not work. Land lines are non-existent,” she added.

Gonzalez communicates with her parents, who live in Maracaibo, when she can “because there is either no internet, no electricity, or no reception.”

According to Gonzalez, Venezuela is worse off than Cuba.

A few years ago, she recalled, a relative of hers flew to the island for physical therapy. “He returned saying that there were no napkins. That they did not eat chicken or meat. There was no toothpaste. And we didn’t believe him. The Cubans would tell him, ‘You are all headed in the same direction, get with it! ... ‘No, that won’t happen here in Venezuela,’ he would respond. And now things are worse.”

A ray of hope shone in January in the form of a massive protest called for by the opposition and led by the president of the National Assembly, Juan Guaidó, who declared himself interim president of Venezuela. He received political backing from the U.S., Canada, Europe and most Latin American countries. A subsequent attempt in February to send a convoy of humanitarian aid from Colombia did not succeed, however, and Nicolás Maduro remains firmly entrenched as president of Venezuela, thanks to a rigged election and manipulation of all the branches of government.

The possibility of change in their home country brings hope to Gonzalez and Mendoza, but at the same time, they are cautious. “We don’t know anymore, we have already endured so much, but it is like the light at the end of the tunnel,” Gonzalez said. “What is happening is important, I have hope.”

KNOW YOUR RIGHTS

Both Gonzalez and Mendoza took part in a “Know Your Rights” discussion on immigration held Feb. 9 at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church in Doral. They wanted to learn about the possibilities of prolonging their legal status in the U.S. or how to go about obtaining asylum.

About 100 people who attended received free legal advice from lawyers with expertise in immigration. The event was organized by the Archdiocese of Miami’s Catholic Legal Services in collaboration with Americans for Immigrant Justice and the Don Bosco Ministry of Our Lady of Guadalupe Church.

The goal was “to guide people, to help them understand how the law works and to see if it is possible for them to qualify for any migratory relief,” said Randolph McGrorty, executive director of Catholic Legal Services.

The Know Your Rights events are important because “we see many immigrants who do not have access to a private lawyer and, because they don’t know any better, a lot of times they fall into the hands of a notary, who does not have a license for legal counseling,” said Ana Quiros, a lawyer with Catholic Legal Services who coordinated the discussion.

Quiros explained that the events are held in different South Florida communities. The conversation in Doral focused on asylum due to the current crisis in Venezuela and the fact that Doral is home to the largest community of Venezuelans in the entire country.

MASSIVE EXODUS

Since 2015, the political, social and economic crisis faced by the South American country has forced the exodus of about 3.3 million Venezuelans to neighboring nations such as Colombia, Peru and Ecuador. According to the United Nations, this is one of the largest exoduses to occur in South America in modern history.

Venezuelans have also departed for the Caribbean, Europe and the U.S., where, until 2017, they made up the second largest group of those requesting asylum (30,000), second only to Peruvians (33,100), according to data from the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees. During the 2018 fiscal year, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services noted more than 21,000 asylum requests from Venezuelans.

But acquiring asylee status in the U.S. is not so simple. Despite the evidence of abuse and violence, poverty, insufficient medicine, and violation of fundamental rights suffered by Venezuelans, “under our laws not all are eligible to receive asylum,” said McGrorty.

Asylum is a form of humanitarian protection for people who have fled their countries for different reasons. The criteria for granting asylum is very strict: “If someone is fleeing it cannot be solely because of poverty,” said Felix Montañez, a lawyer with Catholic Legal Services, during his presentation at the Know Your Rights session.

The law on asylum only protects people who fall into five categories of persecution: race, religion, nationality, political opinion and belonging to a social group. “Many individuals are outside of these categories because we cannot prove that their fears are based on those categories,” the lawyer pointed out.

At the same time, “asylum is a double-edged sword. If you ask for asylum there is the possibility of winning the case and clearing a path toward legal permanent residency and citizenship. But if you lose the case, at the end of the tunnel lies a deportation order,” Montañez warned.

In 2016, the U.S. government granted asylum to 328 Venezuelans, from among more than 14,000 requests. There is no data available for 2017 or 2018.

In the last few years, McGrorty said, the number of solicitations for asylum awaiting processing has piled up, and every year more requests come in. Until last year, the requests were processed by order of arrival; there is a five-year waiting period to receive an interview date. Now, the government is trying to accelerate the process by calling the most recent applicants first.

“That means that people who have waited for years will continue to wait, and those who present their requests now can be called in as little as 30 days,” McGrorty said.

“This eliminates the desire to request asylum if there is not a strong case,” Montañez said. “Many people ask for asylum figuring that even if they are not approved, they can at least obtain a work permit, work legally, save money, and gather evidence.”

To be given a work permit, the asylum request needs to have been pending for six months without causing a delay in the case. Now, appointments are made so quickly that there is not enough time to acquire a work permit.

Not all is lost, however. Other forms of protection can be requested but obtaining them requires the help of a qualified attorney.

There has been much discussion about seeking Temporary Protected Status (TPS), which Venezuelans most definitely qualify for, but according to McGrorty, the current administration is in the process of ending it for other countries. “I think it would be very difficult for Venezuelans to get the current administration to grant them TPS. I wouldn’t say it is impossible, but it is very difficult.”

This article originally appeared in Spanish in the February 2019 edition of La Voz Católica, and online Feb. 23, 2019. Click here for the Spanish.